HISTORY

The Negro Motorist Green Book

Source: Vox Media

(also The Negro Motorist Green Book, The Negro Travelers' Green Book, or simply the Green Book) was an annual guidebook for African-American roadtrippers. It was originated and published by African-American New York City mailman Victor Hugo Green from 1936 to 1966, during the era of Jim Crow laws, when open and often legally prescribed discrimination against African Americans, especially and other non-whites, was widespread. Although pervasive racial discrimination and poverty limited black car ownership, the emerging African-American middle class bought automobiles as soon as they could but faced a variety of dangers and inconveniences along the road, from refusal of food and lodging to arbitrary arrest. In response, Green wrote his guide to services and places relatively friendly to African Americans, eventually expanding its coverage from the New York area to much of North America and founding a travel agency.

Many black Americans took to driving, in part to avoid segregation on public transportation. As the writer George Schuyler put it in 1930, "All Negroes who can do so purchase an automobile as soon as possible in order to be free of discomfort, discrimination, segregation, and insult." [1] Black Americans employed as athletes, entertainers, and salespeople also traveled frequently for work purposes using automobiles that they owned personally.

African-American travelers faced hardships such as white-owned businesses refusing to serve them or repair their vehicles, being refused accommodation or food by white-owned hotels, and threats of physical violence and forcible expulsion from whites-only "sundown towns" Green founded and published the Green Book to avoid such problems, compiling resources "to give the Negro traveler information that will keep him from running into difficulties, embarrassments and to make his trip more enjoyable." [2] The maker of a 2019 documentary film about the book offered this summary: "Everyone I was interviewing talked about the community that the Green Book created: a kind of parallel universe that was created by the book and this kind of secret road map that the Green Book outlined"[3]

From a New York-focused first edition published in 1936, Green expanded the work to cover much of North America, including most of the United States and parts of Canada, Mexico, the Caribbean, and Bermuda. The Green Book became "the bible of black travel during Jim Crow," [4] enabling black travelers to find lodgings, businesses, and gas stations that would serve them along the road. It was little known outside the African-American community. Shortly after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlawed the types of racial discrimination that had made the Green Book unnecessary, publication ceased, and it fell into obscurity. There has been a revived interest in it in the early 21st century in connection with studies of black travel during the Jim Crow era.

Four issues (1940, 1947, 1954, and 1963) have been republished in facsimile (as of December 2017) and have sold well.[5] Twenty-three additional issues have now been digitized by the New York Public Library Digital Collections.[6]

African-American travel experiences

Before the legislative accomplishments of the Civil Rights Movement, black travelers in the United States faced major problems unknown to most whites. White supremacists had long sought to restrict black mobility, and were uniformly hostile to black strangers.

As a result, simple auto journeys for black people were fraught with difficulty and potential danger. They were subjected to racial profiling by police departments ("driving while black"), sometimes seen as "uppity" or "too prosperous" just for the act of driving, which many whites regarded as a white prerogative. They risked harassment or worse on and off the highway.[7] A bitter commentary published in a 1947 issue of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People's magazine, The Crisis, highlighted the uphill struggle blacks faced in recreational travel:

Would a Negro like to pursue a little happiness at a theater, a beach, pool, hotel, restaurant, on a train, plane, or ship, a golf course, summer or winter resort? Would he like to stop overnight at a tourist camp while he motors about his native land 'Seeing America First'? Well, just let him try![8]

Thousands of communities in the US had enacted Jim Crow laws that existed after 1890;[9] in such sundown towns, African-Americans were in danger if they stayed past sunset.[3] Such restrictions dated back to colonial times, and were found throughout the United States. After the end of legal slavery in the North and later in the South after the Civil War, most freedmen continued to live at little more than a subsistence level, but a minority of African-Americans gained a measure of prosperity. They could plan leisure travel for the first time. Well-to-do blacks arranged large group excursions for as many as 2,000 people at a time, for instance traveling by rail from New Orleans to resorts along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico.

In the pre-Jim Crow era this necessarily meant mingling with whites in hotels, transportation and leisure facilities.[10] They were aided in this by the Civil Rights Act of 1875, which had made it illegal to discriminate against African-Americans in public accommodations and public transportation.[11] They encountered a white backlash, particularly in the South, where by 1877 white Democrats controlled every state government. The Act was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court of the United States in 1883, resulting in states and cities passing numerous segregation laws. White governments in the South required even interstate railroads to enforce their segregation laws, despite national legislation requiring equal treatment of passengers.

The Supreme Court of the United States ruled in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) that "separate but equal" accommodations were constitutional, but in practice, facilities for blacks were far from equal, generally being of lesser quality and underfunded. Blacks faced restrictions and exclusion throughout the United States: if not barred entirely from facilities, they could use them only at different times from whites or in (usually inferior) "colored sections".[11]

"Separate but equal" in practice; a separate "Negro Area" at Lewis Mountain in Shenandoah National Park

In 1917, black writer W. E. B. Du Bois observed that the impact of "ever-recurring race discrimination" had made it so difficult to travel to any number of destinations, from popular resorts to major cities, that it was now "a puzzling query as to what to do with vacations".[11] It was a problem that came to affect an increasing number of black people in the first decades of the 20th century. Tens of thousands of southern African-Americans migrated from farms in the south to factories and domestic service in the north. No longer confined to living at a subsistence level, many gained disposable income and time to engage in leisure travel.[10]

The development of affordable mass-produced automobiles liberated black Americans from having to rely on the "Jim Crow cars" – smoky, battered and uncomfortable railroad carriages which were the separate but decidedly unequal alternatives to more salubrious whites-only carriages. One black magazine writer commented in 1933, in an automobile, "it's mighty good to be the skipper for a change, and pilot our craft whither and where we will. We feel like Vikings. What if our craft is blunt of nose and limited of power and our sea is macademized; it's good for the spirit to just give the old railroad Jim Crow the laugh."[10]

Middle-class blacks throughout the United States "were not at all sure how to behave or how whites would behave toward them", as Bart Landry puts it.[12] In Cincinnati, the African-American newspaper editor Wendell Dabney wrote of the situation in the 1920s that "hotels, restaurants, eating and drinking places, almost universally are closed to all people in whom the least tincture of colored blood can be detected".[11] Areas without significant black populations outside the South often refused to accommodate them: black travelers to Salt Lake City in the 1920s were stranded without a hotel if they had to stop there overnight.[10] Only six percent of the more than 100 motels that lined U.S. Route 66 in Albuquerque, admitted black customers.[13] Across the whole state of New Hampshire, only three motels in 1956 served African-Americans.[14]

George Schuyler reported in 1943, "Many colored families have motored all across the United States without being able to secure overnight accommodations at a single tourist camp or hotel." He suggested that black Americans would find it easier to travel abroad than in their own country.[11] In Chicago in 1945, St. Clair Drake and Horace Cayton reported that "the city's hotel managers, by general agreement, do not sanction the use of hotel facilities by Negroes, particularly sleeping accommodations".[15] One incident reported by Drake and Cayton illustrated the discriminatory treatment meted out even to blacks within racially mixed groups:

Two colored schoolteachers and several white friends attended a luncheon at an exclusive coffee shop. The Negro women were allowed to sit down, but the waitress ignored them and served the white women. One of the colored women protested and was told that she could eat in the kitchen.[15]

Role of the Green Book

Segregation meant that facilities for African-American motorists in some areas were limited, but entrepreneurs of varied races realized that opportunities existed in marketing goods and services specifically to black patrons.[10] These included directories of hotels, camps, road houses, and restaurants which would serve African-Americans. Jewish travelers, who had also long experienced discrimination at many vacation spots, created guides for their own community, though they were at least able to visibly blend in more easily with the general population.[30][31] African-Americans followed suit with publications such as Hackley and Harrison's Hotel and Apartment Guide for Colored Travelers, published in 1930[32] to cover "Board, Rooms, Garage Accommodations, etc. in 300 Cities in the United States and Canada".[33] This book was published by Sadie Harrison, who was the Secretary of The Negro Welfare Council (or Negro Urban League).[34]

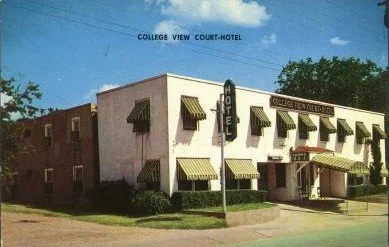

The Green Book listed places, like this motel in South Carolina, that provided accommodation for black travelers

The Negro Motorist Green Book was one of the best known of the African-American travel guides. It was conceived in 1932 and first published in 1936 by Victor H. Green, a World War I veteran from New York City who worked as a mail carrier and later as a travel agent. He said his aim was "to give the Negro traveler information that will keep him from running into difficulties, embarrassments and to make his trip more enjoyable".[2] According to an editorial written by Novera C. Dashiell in the 1956 edition of the Green Book, "the idea crystallized when not only [Green] but several friends and acquaintances complained of the difficulties encountered; oftentimes painful embarrassments suffered which ruined a vacation or business trip".[35]

Green asked his readers to provide information "on the Negro motoring conditions, scenic wonders in your travels, places visited of interest and short stories on one's motoring experience". He offered a reward of one dollar for each accepted account, which he increased to five dollars by 1941.[36] He also obtained information from colleagues in the U.S. Postal Service, who would "ask around on their routes" to find suitable public accommodations.[37] The Postal Service was and remains one of the largest employers of African-Americans, and its employees were ideally situated to inform Green of which places were safe and hospitable to African-American travelers.[38]

The Green Book's motto, displayed on the front cover, urged black travelers to "Carry your Green Book with you – You may need it".[35] The 1949 edition included a quote from Mark Twain: "Travel is fatal to prejudice", inverting Twain's original meaning; as Cotten Seiler puts it, "here it was the visited, rather than the visitors, who would find themselves enriched by the encounter".[39] Green commented in 1940 that the Green Book had given black Americans "something authentic to travel by and to make traveling better for the Negro".[36]

Its principal goal was to provide accurate information on black-friendly accommodations to answer the constant question that faced black drivers: "Where will you spend the night?" As well as essential information on lodgings, service stations and garages, it provided details of leisure facilities open to African Americans, including beauty salons, restaurants, nightclubs and country clubs.[40] The listings focused on four main categories – hotels, motels, tourist homes (private residences, usually owned by African-Americans, which provided accommodation to travelers), and restaurants. They were arranged by state and subdivided by city, giving the name and address of each business. For an extra payment, businesses could have their listing displayed in bold type or have a star next to it to denote that they were "recommended".[14]

Many such establishments were run by and for African-Americans and in some cases were named after prominent figures in African-American history. In North Carolina, such black-owned businesses included the Carver, Lincoln, and Booker T. Washington hotels, the Friendly City beauty parlor, the Black Beauty Tea Room, the New Progressive tailor shop, the Big Buster tavern, and the Blue Duck Inn.[41] Each edition also included feature articles on travel and destinations,[42] and included a listing of black resorts such as Idlewild, Michigan; Oak Bluffs, Massachusetts; and Belmar, New Jersey.[43] The state of New Mexico was particularly recommended as a place where most motels would welcome "guests on the basis of 'cash rather than color'".[37]

Influence

The Green Book attracted sponsorship from a great number of businesses, including the African-American newspapers Call and Post of Cleveland, and the Louisville Leader of Louisville.[44] Esso (later ExxonMobil), was also a sponsor, due in part to the efforts of a pioneering African-American Esso sales representative named James "Billboard" Jackson.[36] Additionally, Esso had a black focused marketing division promote the Green Bookas enabling Esso's black customers to "go further with less anxiety."[45] By contrast, Shell gas stations were known to refuse black customers.[46]

The College View Court-Hotel in Waco, Texas, advertised as "Waco's Finest for Negroes" in the 1950s

The 1949 edition included an Esso endorsement message that told readers: "As representatives of the Esso Standard Oil Co., we are pleased to recommend the Green Book for your travel convenience. Keep one on hand each year and when you are planning your trips, let Esso Touring Service supply you with maps and complete routings, and for real 'Happy Motoring' – use Esso Products and Esso Service wherever you find the Esso sign."[13] Photographs of some African-American entrepreneurs who owned Esso gas stations appeared in the pages of the Green Book.[37]

Although Green usually refrained from editorializing in the Green Book, he let his readers' letters speak for the influence of his guide. William Smith of Hackensack, New Jersey, described it as a "credit to the Negro Race" in a letter published in the 1938 edition. He commented:

It is a book badly needed among our Race since the advent of the motor age. Realizing the only way we knew where and how to reach our pleasure resorts was in a way of speaking, by word of mouth, until the publication of The Negro Motorist Green Book ... We earnestly believe that [it] will mean as much if not more to us as the A.A.A. means to the white race.[44]

The "Colored only" Hotel Clark in Memphis, Tennessee, c. 1939

Earl Hutchinson Sr., the father of journalist Earl Ofari Hutchinson, wrote of a 1955 move from Chicago to California that "you literally didn't leave home without [the Green Book]".[47] Ernest Green, one of the Little Rock Nine, used the Green Book to navigate the 1,000 miles (1,600 km) from Arkansas to Virginia in the 1950s and comments that "it was one of the survival tools of segregated life".[48] According to the civil rights leader Julian Bond, recalling his parents' use of the Green Book, "it was a guidebook that told you not where the best places were to eat, but where there was any place".[49] Bond comments:

You think about the things that most travelers take for granted, or most people today take for granted. If I go to New York City and want a hair cut, it's pretty easy for me to find a place where that can happen, but it wasn't easy then. White barbers would not cut black peoples' hair. White beauty parlors would not take black women as customers — hotels and so on, down the line. You needed the Green Book to tell you where you can go without having doors slammed in your face.[31]

While the Green Book was intended to make life easier for those living under Jim Crow, its publisher looked forward to a time when such guidebooks would no longer be necessary. As Green wrote, "there will be a day sometime in the near future when this guide will not have to be published. That is when we as a race will have equal opportunities and privileges in the United States. It will be a great day for us to suspend this publication for then we can go as we please, and without embarrassment."[47]

Los Angeles is now considering offering special protection to the sites that kept black travelers safe. Ken Bernstein, principal planner for the city's Office of Historic Resources notes, "At the very least, these sites can be incorporated into our city's online inventory system. They are part of the story of African Americans in Los Angeles, and the story of Los Angeles itself writ large."[50]

Digital projects

The New York Public Library's Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture has published digitized copies of 21 issues of the Green Book, dating from 1937 to 1966–1967. To accompany the digitizations, the NYPL Labs have developed an interactive visualization of the books' data to enable web users to plot their own road trips and see heat maps of listings.[61]

The Green Book Project, with an endorsement from the Tulsa City-County Library's African American Resource Center, created a digital map of the Green Book locations on historypin, invited users of the Green Book to post their photos and personal accounts about Green Book sites.[62]

Exhibitions

In 2003, the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of American History included the Green Book in an exhibition, America on the Move.

In 2007, the book was featured in a traveling exhibition called Places of Refuge: The Dresser Trunk Project, organized by William Daryl Williams, the director of the School of Architecture and Interior Design at the University of Cincinnati. The exhibition drew on the Green Book to highlight artifacts and locations associated with travel by blacks during segregation, using dresser trunks to reflect venues such as hotels, restaurants, nightclubs and a Negro league baseball park.[58]

In late 2014, the Gilmore Car Museum in Hickory Corners, Michigan, installed a permanent exhibit on the Green Book that features a 1956 copy of the book that guests can review as well as video interviews of those that utilized it.[63]

In 2016, a 1941 copy of the book was displayed at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, when the museum opened.[37]

In June 2016, a copy of the book on loan from The New York Public Library was featured in the Missouri History Museum's exhibition Main Street Through St. Louis.[64]

A copy of the book is featured in the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum's temporary exhibition, Get in the Game: The Fight for Equality in American Sports, on view April 2018 through January 13, 2019.[65]

Films

Calvin Alexander Ramsey and Becky Wible Searles interviewed people who traveled with the Green Book as well as Victor Green's relatives as part of the production of the documentary The Green Book Chronicles (2016).[66]

100 Miles to Lordsburg (2015) is a short film, written by Phillip Lewis and producer Brad Littlefield, and directed by Karen Borger. It is about a black couple crossing New Mexico in 1961 with aid of the Green Book.[67] Set in 1961, Jack and Martha, a young, African-American couple, are driving across country heading to a new life in California. Jack, a Korean War Vet, and Monique, his heavily pregnant wife use the travel guide "The Negro Motorist Green Book". Turned away from the first motel in Las Cruces, NM they must drive 100 miles to the next town Lordsburg, NM. On the way, their car breaks down. The film achieved festival success during 2016.

The 2018 drama film Green Book centers a professional tour of the South taken by Don Shirley, a black musician, and his chauffeur, Tony Vallelonga, who use the book to find lodgings and eateries where they can do business. In so doing, Vallelonga learns about the various racist indignities and dangers his employer must endure, which he shares himself to a lesser extent for being Italian-American.

The documentary film The Green Book: Guide to Freedom by Yoruba Richen was scheduled to first air on February 25, 2019, on the Smithsonian Channel in the US.[68][69][70]

The 2019 virtual reality documentary Traveling While Black places the viewer directly inside a portrait of African American travelers making use of the Green Book.[71]

Literature

Ramsey also wrote a play, called The Green Book: A Play in Two Acts, which debuted in Atlanta in August 2011[54] after a staged reading at the Lincoln Theatre in Washington, DC in 2010.[4] It centers on a tourist home in Jefferson City, Missouri. A black military officer, his wife, and a Jewish survivor of the Holocaust spend the night in the home just before the civil rights activist W. E. B. Du Bois is scheduled to deliver a speech in town. The Jewish traveler comes to the home after being shocked to find that the hotel where he planned to stay has a "No Negroes Allowed" notice posted in its lobby—an allusion to the problems of discrimination that Jews and blacks both faced at the time.[49] The play was highly successful, gaining an extension of several weeks beyond its planned closing date.[58]

Matt Ruff's horror-fantasy novel Lovecraft Country (2016) (set in Chicago) features a fictionalized version of Green and the Travel Guide known as the "Safe Negro Travel Guide". The guide is also depicted in the HBO adaptation of the same name Lovecraft Country

In Toni Morrison's Home (2012), the narrator makes a brief reference to the Green Book: "From Green's travelers' book he copies out some addresses and names of rooming houses, hotels where he would not be turned away" (pp. 22–23).

A 2017 nonfiction work entitled The Post-Racial Negro Green Book (Brown Bird Books) makes use of the original Green Book's format and aesthetic as a medium for cataloging 21st century racism toward African Americans.

A 2019 nonfiction essay by Tiffany Marie Tucker entitled "Picture Me Rollin" considers the Green Book and her own movement in and throughout modern Chicago.

Photography projects

Architecture at sites listed in the Green Book is being documented by photographer Candacy Taylor in collaboration with the National Park Service's Route 66 Corridor Preservation Program.[72][73]She is planning to publish other materials and apps featuring such sites.[37]